People Don’t Need Rescuing

Rescuing sounds like such a positive thing to do: heroic, compassionate, Christlike. And much in our culture encourages us to become rescuers, even to adopt the persona of the Rescuer as our own. Our myths, legends and fairy tales are full of brave and resourceful people rescuing the weak and the vulnerable. And all of them are constantly recycled in our TV shows and films.

These stories are embedded in our collective consciousness and because of this they have a profound effect on our sponge-like and developing personalities as children. We see in them an ideal to aspire to, and a ready-made answer to the impossibly difficult question of how to be in the world. Many of us, therefore, have from a very early age assumed a heroic and romantic view of our relationships with others: they can be the victim, the helpless and hapless one in need of rescuing and we can be the hero, the one who sorts everything out and makes it OK. Once this early decision is made it is then very possible for us to go

through life with this Rescuer self-image, always looking to put right what others can’t, and struggling to relate to anyone other than as a Rescuer to a Victim.

In this way we are primed from an early age to see the ministry and other caring professions in a romantic and heroic light. This is reinforced by models of ministry and service that cast the church leader or the ideal Christian as a person who does things for others, who sorts out their problems and conjures solutions to situations that tie others up in knots. The ideal Christian does not carry someone else’s burden with them, they carry it for them. The ideal Christian is the Knight in Shining Armour made flesh.

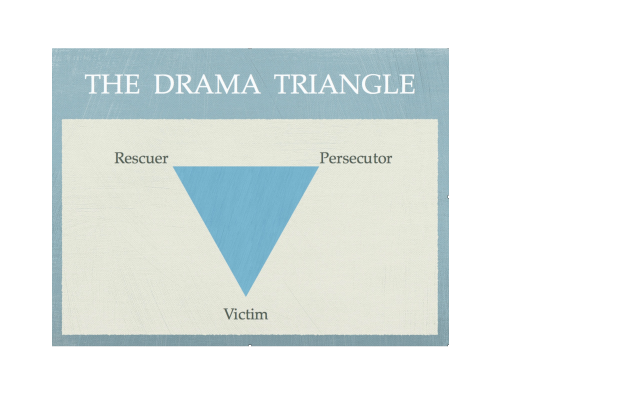

However, as Transactional Analysis (TA) theory shows, rescuing is one part of a doomed pattern of relating. TA contains a very simple but powerful tool for analysing relationships called the Drama Triangle.

This suggests that there are three identities to which we are all drawn. Some of us are inclined to assume the identity of the Victim, others the Persecutor and still others the Rescuer. We then become locked in a pattern of relating that is constricted and inflexible and that can never lead to true intimacy.

This suggests that there are three identities to which we are all drawn. Some of us are inclined to assume the identity of the Victim, others the Persecutor and still others the Rescuer. We then become locked in a pattern of relating that is constricted and inflexible and that can never lead to true intimacy.

Those of us whose identities are tied up with victimhood will never relate to others as a complete self, but only as a two-dimensional character seeking to attract the heroism or the abuse of others either of which reinforces our identity as a Victim. We relate to others in this way out of a belief that they are better then us: they deserve to be here; they deserve respect; they deserve to be loved, but we don’t.

We who assume the relational role of Persecutor on the other hand are convinced that it is we and not others who are OK. From our one-up position we are able to look down on the Victim and the Rescuer alike and try to force them to correct their erroneous ways. Judgemental and critical, everything will only be OK if everyone else changes.

Rescuers share this exalted position with the Persecutor. Like the Persecutor we Rescuers believe that others are not OK, that they are unable to cope, incapable of solving their own problems and incompetent to thrive in the world. We discount not only their potency, but also their worth and it is important that we do so, since that is the only way we can protect our belief that we’re OK. And, of course, our belief that we’re OK can only be sustained by the corresponding belief that others are not. However, the sad truth about this need to occupy a one-up position in our relationships is that it arises from a need to escape the painful and therefore suppressed belief that we are not OK. So long as we can convince ourselves that others are not OK – by constantly rescuing them – then we can escape our own vulnerability and sense of shame.

A further factor in the creation of the Rescuer persona is a fear of intimacy. We engage with the other in order to achieve intimacy but default into a rescuing role because we believe that is the only way we will be accepted by others. For this reason being a Rescuer can never really bring relational fulfilment or satisfaction. We are left feeling empty and dissatisfied by our relationships; a feeling that will ultimately provoke us to switch roles, from Rescuer to Persecutor, or perhaps to Victim from where we can temporarily look for our own Rescuer until such time as we feel fit to put on our shining armour once more.

It is worth pointing out that this Rescuer-Victim relationship has another fault line running through it which is the unwillingness of the Victim to be rescued. This may seem contradictory since, as I’ve pointed out, the Victim is on the lookout for a Rescuer. But as soon as the Victim allows the Rescuer to successfully intervene then they can no longer be a Victim, and being a Victim is essential to their self-definition. It is their identity and to surrender it is more threatening than whatever it is from which the Rescuer thinks they need saving.

It’s easy then to see why Rescuers are attracted to the ministry. Few positions in society allow an individual to assume a one-up position more readily than the stereotypical church minister. In a position of authority that commands respect, the minister is also a figure to whom others look for help. Like a child lets loose in a sweet shop the Rescuer minister has a congregation of people who can easily be cast in the role of Victim, people he can use to bolster his belief that he is OK and they are not. From his pulpit he can tell them what’s wrong with them and what they need to do to sort it out and in their homes he can be the one whose prayer is highly prized, the intercessor who has the ear of God.

It also allows a person to hide from real relationships of intimacy behind the mask of the ministerial persona. We ministers don’t have to be ourselves, in fact it can often be the case that others don’t want us to be ourselves, demanding instead that we conform to the stereotype. We are then required us to live the public life of a pseudo personality within which we are never truly threatened by the challenge of intimacy. None of this is sustainable of course, nor is it a Biblical model for ministry.

It is clearly true that on times people really do need to be helped. What I am drawing attention to here is not the act of helping people because of their need, but rather the compulsion to help people because of the need of the helper to help. This is not what Christ taught or modelled. It is not love.

When I attempt to rescue another with the out-of-awareness motivation to sustain a false identity rather than as a genuine response to an actual need they have, then I am failing to love them. Instead of being respected the other is being discounted. To be Christlike is to empower Victims, Rescuers and Persecutors alike to choose to transcend their self-defeating self-image (even as I am being delivered from enslavement to my own self-image as a Rescuer, Viti). And the only way I can influence this is if I step outside of my familiar role of Rescuer and respect the other person’s capacity to think and act for themselves, to convey God’s unconditional acceptance of them through my own welcoming of them into my life as they are.

Spot on Owen. That’s us.

LikeLiked by 1 person

An interesting classification of the tendencies we fall into as a result of our own inadequacies, environment or will.Perhaps we’re vulnerable (or desire) to be a mixture of all three traits depending on our circumstances such as health, wellbeing, relationships and experiences in life.

For some reason after my first reading of this very thought and discussion provoking blog, Micah 6 v.8 came to mind.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think we do have the capacity to be a Victim, Persecutor and a Rescuer, but we will certainly have a favourite which we will try to use to shape all our relationships. We will also have a second favourite role to inhabit, which we assume when we feel we are getting frustrated in our attempts to inhabit our primary role.

LikeLike

A very thought provoking blog in terms of what perils await a minister who is focused on self and lacking humility. The thought that a minister can ‘change people’ or sort their problems must be a significant burden on those who carry such thoughts.

Reading your blog raised the thought in my mind of; if one analyses ones motives for everything we do, it could be a great reason to do nothing. Could I be tempted to think who is gaining from this action; me because of my ego, or the other party as I bestow my wisdom/resources on them, or am I putting myself in a position to be exploited. Perhaps it could be a good excuse, because people are empowered to sort out their own problems given time, not to get involved. I have found this a great option in the past.

I have, over the years, experienced the traits you have identified in ministers so I have come to realise they are ‘normal’ people with all the failings the rest of us have. They are restrained by position, fear of displaying favouritism in the congregation or even their own fear of showing they don’t know it all. This has led me not to expect a great deal but to take pleasure in being surprised when they come up with the goods. (I was going to put trumps but in the present climate it wouldn’t add anything). And I am on many occasions surprised when they drop their guard that they too expose struggles and needs and their human side.

Recognising that we as Christians are no different in all the blessings and responsibilities we enjoy to the minister; but by the very act of taking on the role of an ‘under-shepherd’ and being paid by the congregation to lead them is it surprising that we as congregations expect certain things? However, he is not a substitute for social services, or the local maintenance man. We are all warned about judging others but we do need discernment as we deal with people as every circumstance is different. It will be interesting how your ‘lessons’ materialise over the coming years.

If I have missed the point then forgive me.

LikeLike

I think it’s a fair point you make that introspection will lead to inactivity. I would suggest, however, that it is advisable to search our motives (in conversation with someone else, by the way) when we become aware of a pattern of behaviour that is disruptive and unhelpful. Finding excuses not to get involved in life would be one possible example of such a pattern. I also agree that there is a great deal of pressure put on ministers to be different from others. Theologically, I suggest this is abandoning of the Reformers’ assertion that there is no such thing as an especially sanctified vocation, and that whatever career the saint pursues is sacred by virtue of the fact that it is a saint who pursues it. Secondly, I suspect that there remains a psychological need on the part of some to have a figure of special authority and power in order to provide them with a sense of stability in a frightening world. I would also suggest that this appeals to a certain psyche that wishes to construct a false self in order to defend the very vulnerable real self. The ministry offers a golden opportunity then for people to hide from their true vulnerability.

LikeLike